ScaryClown bellyRubsTheClown = new ScaryClown();

bellyRubsTheClown.balloonCount();

// => 0

bellyRubsTheClown.receiveBalloons(2);

bellyRubsTheClown.balloonCount();

// => 2

bellyRubsTheClown.makeBalloonArt();

// => "Belly Rubs makes a balloon shaped like a clown, because Belly Rubs

// => is trying to scare you and nothing is scarier than clowns."

Working with the JVM

There comes a day in every Clojurist’s life when she must venture forth from the sanctuary of pure functions and immutable data structures into the wild, barbaric Land of Java. This treacherous journey is necessary because Clojure is hosted on the Java Virtual Machine ( JVM), which

grants it three fundamental characteristics. First, you run Clojure applications the same way you run Java applications. Second, you need to use Java objects for core functionality like reading files and working with dates. Third, Java has a vast ecosystem of useful libraries, and you’ll need to know a bit about Java to use them.

In this way, Clojure is a bit like a utopian community plunked down in the middle of a dystopian country. Obviously you’d prefer to interact with other utopians, but every once in a while you need to talk to the locals in order to get things done.

This chapter is like a cross between a phrase book and cultural introduction for the Land of Java. You’ll learn what the JVM is, how it runs programs, and how to compile programs for it. This chapter will also give you a brief tour of frequently used Java classes and methods, and explain how to interact with them using Clojure. You’ll learn how to think about and understand Java so you can incorporate any Java library into your Clojure programs.

To run the examples in this chapter, you’ll need to have the Java Development Kit ( JDK) version 1.6 or later installed on your computer. You can check by running javac -version at your terminal. You should see something like java 1.8.0_40; if you don’t, visit http://www.oracle.com/ to download the latest JDK.

The JVM

Developers use the term JVM to refer to a few different things. You’ll hear them say, “Clojure runs on the JVM,” and you’ll also hear, “Clojure programs run in a JVM.” In the first case, JVM refers to an abstraction—the general model of the Java Virtual Machine. In the second, it refers to a process—an instance of a running program. We’ll focus on the JVM model, but I’ll point out when we’re talking about running JVM processes.

To understand the JVM, let’s step back and review how plain ol’ computers work. Deep in the cockles of a computer’s heart is its CPU, and the CPU’s job is to execute operations like add and unsigned multiply. You’ve probably heard about programmers encoding these instructions on punch cards, in lightbulbs, in the sacred cracks of a tortoise shell, or whatever, but nowadays these operations are represented in assembly language by mnemonics like ADD and MUL. The CPU architecture (x86, ARMv7, and what have you) determines what operations are available as part of the architecture’s instruction set.

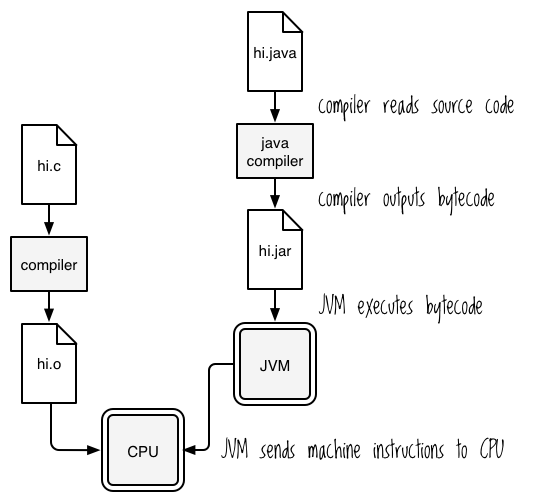

Because it’s no fun to program in assembly language, people have invented higher-level languages like C and C++, which are compiled into instructions that a CPU will understand. Broadly speaking, the process is:

- The compiler reads source code.

- The compiler outputs a file containing machine instructions.

- The CPU executes those instructions.

Notice in Figure 12-1 that, ultimately, you have to translate programs into instructions that a CPU will understand, and the CPU doesn’t care which programming language you use to produce those instructions.

The JVM is analogous to a computer in that it also needs to translate code into low-level instructions, called Java bytecode. However, as a virtual machine, this translation is implemented as software rather than hardware. A running JVM executes bytecode by translating it on the fly into machine code that its host will understand, a process called just-in-time compilation.

For a program to run on the JVM, it must get compiled to Java bytecode. Usually, when you compile programs, the resulting bytecode is saved in a .class file. Then you’ll package these files in Java archive files ( JAR files). And just like how a CPU doesn’t care which programming language you use to generate machine instructions, the JVM doesn’t care how you create bytecode. It doesn’t care if you use Scala, JRuby, Clojure, or even Java to create Java bytecode. Generally speaking, the process looks like that shown in Figure 12-2.

- The Java compiler reads source code.

- The compiler outputs bytecode, often to a JAR file.

- JVM executes the bytecode.

- The JVM sends machine instructions to the CPU.

When someone says that Clojure runs on the JVM, one of the things they mean is that Clojure programs get compiled to Java bytecode and JVM processes execute them. From an operations perspective, this means you treat Clojure programs the same as Java programs. You compile them to JAR files and run them using the java command. If a client needs a program that runs on the JVM, you could secretly write it in Clojure instead of Java and they would be none the wiser. From the outside, you can’t tell the difference between a Java and a Clojure program any more than you can tell the difference between a C and a C++ program. Clojure allows you to be productive and sneaky.

Writing, Compiling, and Running a Java Program

Let’s look at how a real Java program works. In this section, you’ll learn about the object-oriented paradigm that Java uses. Then, you’ll build a simple pirate phrase book using Java. This will help you feel more comfortable with the JVM, it will prepare you for the upcoming section on Java interop (writing Clojure code that uses Java classes, objects, and methods directly), and it’ll come in handy should a scallywag ever attempt to scuttle your booty on the high seas. To tie all the information together, you’ll take a peek at some of Clojure’s Java code at the end of the chapter.

Object-Oriented Programming in the World’s Tiniest Nutshell

Java is an object-oriented language, so you need to understand how object-oriented programming (OOP) works if you want to understand what’s happening when you use Java libraries or write Java interop code in your Clojure programming. You’ll also find object-oriented terminology in Clojure documentation, so it’s important to learn these concepts. If you’re OOP savvy, feel free to skip this section. For those who need the two-minute lowdown, here it is: the central players in OOP are classes, objects, and methods.

I think of objects as really, really, ridiculously dumb androids. They’re the kind of android that would never inspire philosophical debate about the ethics of forcing sentient creatures into perpetual servitude. These androids only do two things: they respond to commands and they maintain data. In my imagination they do this by writing stuff down on little Hello Kitty clipboards.

Imagine a factory that makes these androids. Both the set of commands the android understands and the set of data it maintains are determined by the factory that makes the android. In OOP terms, the factories correspond to classes, the androids correspond to objects, and the commands correspond to methods. For example, you might have a ScaryClown factory (class) that produces androids (objects) that respond to the command (method) makeBalloonArt. The android keeps track of the number of balloons it has, and then updates that number whenever the number of balloons changes. It can report that number with balloonCount and receive any number of balloons with receiveBalloons. Here’s how you might interact with a Java object representing Belly Rubs the Clown:

This example shows you how to create a new object, bellyRubsTheClown, using the ScaryClown class. It also shows you how to call methods (such as balloonCount, receiveBalloons, and makeBalloonArt) on the object, presumably so you can terrify children.

One final aspect of OOP that you should know, or at least how it’s implemented in Java, is that you can also send commands to the factory. In OOP terms, you would say that classes also have methods. For example, the built-in class Math has many class methods, including Math.abs, which returns the absolute value of a number:

Math.abs(-50)

// => 50

I hope those clowns weren’t too traumatizing for you. Now let’s put your OOP knowledge to work!

Ahoy, World

Go ahead and create a new directory called phrasebook. In that directory, create a file called PiratePhrases.java, and write the following:

public class PiratePhrases

{

public static void main(String[] args)

{

System.out.println("Shiver me timbers!!!");

}

}

This very simple program will print the phrase “Shiver me timbers!!!” (which is how pirates say “Hello, world!”) to your terminal when you run it. It consists of a class, PiratePhrases, and a static method belonging to that class, main. Static methods are essentially class methods.

In your terminal, compile the PiratePhrases source code with the command javac PiratePhrases.java. If you typed everything correctly and you’re pure of heart, you should see a file named PiratePhrases.class:

$ ls

PiratePhrases.class PiratePhrases.java

You’ve just compiled your first Java program, me matey! Now run it with java PiratePhrases. You should see this:

Shiver me timbers!!!

What’s happening here is you used the Java compiler, javac, to create a Java class file, PiratePhrases.class. This file is packed with oodles of Java bytecode (well, for a program this size, maybe only one oodle).

When you ran java PiratePhrases, the JVM first looked at your classpath for a class named PiratePhrases. The classpath is the list of filesystem paths that the JVM searches to find a file that defines a class. By default, the classpath includes the directory you’re in when you run java. Try running java -classpath /tmp PiratePhrases and you’ll get an error, even though PiratePhrases.class is right there in your current directory.

Note You can have multiple paths on your classpath by separating them with colons if you’re on a Mac or running Linux, or semicolons if you’re using Windows. For example, the classpath /tmp:/var/maven:. includes the /tmp, /var/maven, and . directories.

In Java, you’re allowed only one public class per file, and the filename must match the class name. This is how java knows to try looking in PiratePhrases.class for the PiratePhrases class’s bytecode. After java found the bytecode for the PiratePhrases class, it executed that class’s main method. Java’s similar to C in that whenever you say “run something, and use this class as your entry point,” it will always run that class’s main method; therefore, that method must be public, as you can see in the PiratePhrases’s source code.

In the next section you’ll learn how to handle program code that spans multiple files, and how to use Java libraries.

Packages and Imports

To see how to work with multi-file programs and Java libraries, we’ll compile and run a program. This section has direct implications for Clojure because you’ll use the same ideas and terminology to interact with Java libraries.

Let’s start with a couple of definitions:

-

package Similar to Clojure’s namespaces, packages provide code organization. Packages contain classes, and package names correspond to filesystem directories. If a file has the line

package com.shapemasterin it, the directory com/shapemaster must exist somewhere on your classpath. Within that directory will be files defining classes. -

import Java allows you to import classes, which basically means that you can refer to them without using their namespace prefix. So if you have a class in

com.shapemasternamedSquare, you could writeimportcom.shapemaster.Square;orimport com.shapemaster.*;at the top of a.javafile to useSquarein your code instead ofcom.shapemaster.Square.

Let’s try using package and import. For this example, you’ll create a package called pirate_phrases that has two classes, Greetings and Farewells. To start, navigate to your phrasebook and within that directory create another directory, pirate_phrases. It’s necessary to create pirate_phrases because Java package names correspond to filesystem directories. Then, create Greetings.java within the pirate_phrases directory:

➊ package pirate_phrases;

public class Greetings

{

public static void hello()

{

System.out.println("Shiver me timbers!!!");

}

}

At ➊, package pirate_phrases; indicates that this class will be part of the pirate_phrases package. Now create Farewells.java within the pirate_phrases directory:

package pirate_phrases;

public class Farewells

{

public static void goodbye()

{

System.out.println("A fair turn of the tide ter ye thar, ye magnificent sea friend!!");

}

}

Now create PirateConversation.java in the phrasebook directory:

import pirate_phrases.*;

public class PirateConversation

{

public static void main(String[] args)

{

Greetings greetings = new Greetings();

greetings.hello();

Farewells farewells = new Farewells();

farewells.goodbye();

}

}

The first line, import pirate_phrases.*;, imports all classes in the pirate_phrases package, which contains the Greetings and Farewells classes.

If you run javac PirateConversation.java within the phrasebook directory followed by java PirateConversation, you should see this:

Shiver me timbers!!!

A fair turn of the tide ter ye thar, ye magnificent sea friend!!

And thar she blows, dear reader. Thar she blows indeed.

Note that, when you’re compiling a Java program, Java searches your classpath for packages. Try typing the following:

cd pirate_phrases

javac ../PirateConversation.java

You’ll get this:

../PirateConversation.java:1: error: package pirate_phrases does not exist

import pirate_phrases.*;

^

Boom! The Java compiler just told you to hang your head in shame and maybe weep a little.

Why? It thinks that the pirate_phrases package doesn’t exist. But that’s stupid, right? You’re in the pirate_phrases directory!

What’s happening here is that the default classpath only includes the current directory, which in this case is pirate_phrases. javac is trying to find the directory phrasebook/pirate_phrases/pirate_phrases, which doesn’t exist. When you run javac ../PirateConversation.java from within the phrasebook directory, javac tries to find the directory phrasebook/pirate_phrases, which does exist. Without changing directories, try running javac -classpath ../ ../PirateConversation.java. Shiver me timbers, it works! This works because you manually set the classpath to the parent directory of pirate_phrases, which is phrasebook. From there, javac can successfully find the pirate_phrases directory.

In summary, packages organize code and require a matching directory structure. Importing classes allows you to refer to them without having to prepend the entire class’s package name. javac and Java find packages using the classpath.

JAR Files

JAR files allow you to bundle all your .class files into one single file. Navigate to your phrasebook directory and run the following:

jar cvfe conversation.jar PirateConversation PirateConversation.class

pirate_phrases/*.class

java -jar conversation.jar

This displays the pirate conversation correctly. You bundled all the class files into conversation.jar. Using the e flag, you also indicated that the PirateConversation class is the entry point. The entry point is the class that contains the main method that should be executed when the JAR as a whole runs, and jar stores this information in the file META-INF/MANIFEST.MF within the JAR file. If you were to read that file, it would contain this line:

Main-Class: PirateConversation

By the way, when you execute JAR files, you don’t have to worry which directory you’re in, relative to the file. You could change to the pirate_phrases directory and run java -jar ../conversation.jar, and it would work fine. The reason is that the JAR file maintains the directory structure. You can see its contents with jar tf conversation.jar, which outputs this:

META-INF/

META-INF/MANIFEST.MF

PirateConversation.class

pirate_phrases/Farewells.class

pirate_phrases/Greetings.class

You can see that the JAR file includes the pirate_phrases directory. One more fun fact about JARs: they’re really just ZIP files with a .jar extension. You can treat them the same as any other ZIP file.

clojure.jar

Now you’re ready to see how Clojure works under the hood! Download the 1.9.0 stable release and run it:

java -jar clojure-1.9.0.jar

You should see the most soothing of sights, the Clojure REPL. How did it actually start up? Let’s look at META-INF/MANIFEST.MF in the JAR file:

Manifest-Version: 1.0

Archiver-Version: Plexus Archiver

Created-By: Apache Maven

Built-By: hudson

Build-Jdk: 1.7.0_20

Main-Class: clojure.main

It looks like clojure.main is specified as the entry point. Where does this class come from? Well, have a look at clojure/main.java on GitHub at https://github.com/clojure/clojure/blob/master/src/jvm/clojure/main.java:

/**

* Copyright (c) Rich Hickey. All rights reserved.

* The use and distribution terms for this software are covered by the

* Eclipse Public License 1.0 (http://opensource.org/licenses/eclipse-1.0.php)

* which can be found in the file epl-v10.html at the root of this distribution.

* By using this software in any fashion, you are agreeing to be bound by

* the terms of this license.

* You must not remove this notice, or any other, from this software.

**/

package clojure;

import clojure.lang.Symbol;

import clojure.lang.Var;

import clojure.lang.RT;

public class main{

final static private Symbol CLOJURE_MAIN = Symbol.intern("clojure.main");

final static private Var REQUIRE = RT.var("clojure.core", "require");

final static private Var LEGACY_REPL = RT.var("clojure.main", "legacy-repl");

final static private Var LEGACY_SCRIPT = RT.var("clojure.main", "legacy-script");

final static private Var MAIN = RT.var("clojure.main", "main");

public static void legacy_repl(String[] args) {

REQUIRE.invoke(CLOJURE_MAIN);

LEGACY_REPL.invoke(RT.seq(args));

}

public static void legacy_script(String[] args) {

REQUIRE.invoke(CLOJURE_MAIN);

LEGACY_SCRIPT.invoke(RT.seq(args));

}

public static void main(String[] args) {

REQUIRE.invoke(CLOJURE_MAIN);

MAIN.applyTo(RT.seq(args));

}

}

As you can see, the file defines a class named main. It belongs to the package clojure and defines a public static main method, and the JVM is completely happy to use it as an entry point. Seen this way, Clojure is a JVM program just like any other.

This wasn’t meant to be an in-depth Java tutorial, but I hope that it helped clarify what programmers mean when they talk about Clojure “running on the JVM” or being a “hosted” language. In the next section, you’ll continue to explore the magic of the JVM as you learn how to use additional Java libraries within your Clojure project.

Clojure App JARs

You now know how Java runs Java JARs, but how does it run Clojure apps bundled as JARs? After all, Clojure applications don’t have classes, do they?

As it turns out, you can make the Clojure compiler generate a class for a namespace by putting the (:gen-class) directive in the namespace declaration. (You can see this in the very first Clojure program you created, clojure-noob in Chapter 1. Remember that program, little teapot?) This means that the compiler produces the bytecode necessary for the JVM to treat the namespace as if it defines a Java class.

You set the namespace of the entry point for your program in the program’s project.clj file, using the :main attribute. For clojure-noob, you should see :main ^:skip-aot clojure-noob.core. When Leiningen compiles this file, it will add a meta-inf/manifest.mf file that contains the entry point to the resulting JAR file.

So, if you define a -main function in a namespace and include the (:gen-class) directive, and also set :main in your project.clj file, your program will have everything it needs for Java to run it when it gets compiled as a JAR. You can try this out in your terminal by navigating to your clojure-noob directory and running this:

lein uberjar

java -jar target/uberjar/clojure-noob-0.1.0-SNAPSHOT-standalone.jar

You should see two messages printed out: “Cleanliness is next to godliness” and “I’m a little teapot!” Note that you don’t need Leiningen to run the JAR file; you can send it to friends and neighbors and they can run it as long as they have Java installed.

Java Interop

One of Rich Hickey’s design goals for Clojure was to create a practical language. For that reason, Clojure was designed to make it easy for you to interact with Java classes and objects, meaning you can use Java’s extensive native functionality and its enormous ecosystem. The ability to use Java classes, objects, and methods is called Java interop. In this section, you’ll learn how to use Clojure’s interop syntax, how to import Java packages, and how to use the most frequently used Java classes.

Interop Syntax

Using Clojure’s interop syntax, interacting with Java objects and classes is straightforward. Let’s start with object interop syntax.

You can call methods on an object using (.methodName object). For example, because all Clojure strings are implemented as Java strings, you can call Java methods on them:

(.toUpperCase "By Bluebeard's bananas!")

; => "BY BLUEBEARD'S BANANAS!"

➊ (.indexOf "Let's synergize our bleeding edges" "y")

; => 7

These are equivalent to this Java:

"By Bluebeard's bananas!".toUpperCase()

"Let's synergize our bleeding edges".indexOf("y")

Notice that Clojure’s syntax allows you to pass arguments to Java methods. In this example, at ➊ you passed the argument "y" to the indexOf method.

You can also call static methods on classes and access classes’ static fields. Observe!

➊ (java.lang.Math/abs -3)

; => 3

➋ java.lang.Math/PI

; => 3.141592653589793

At ➊ you called the abs static method on the java.lang.Math class, and at ➋ you accessed that class’s PI static field.

All of these examples (except java.lang.Math/PI) use macros that expand to use the dot special form. In general, you won’t need to use the dot special form unless you want to write your own macros to interact with Java objects and classes. Nevertheless, here is each example followed by its macroexpansion:

(macroexpand-1 '(.toUpperCase "By Bluebeard's bananas!"))

; => (. "By Bluebeard's bananas!" toUpperCase)

(macroexpand-1 '(.indexOf "Let's synergize our bleeding edges" "y"))

; => (. "Let's synergize our bleeding edges" indexOf "y")

(macroexpand-1 '(Math/abs -3))

; => (. Math abs -3)

This is the general form of the dot operator:

(. object-expr-or-classname-symbol method-or-member-symbol optional-args*)

The dot operator has a few more capabilities, and if you’re interested in exploring it further, you can look at clojure.org’s documentation on Java interop at http://clojure.org/java_interop#Java%20Interop-The%20Dot%20special%20form.

Creating and Mutating Objects

The previous section showed you how to call methods on objects that already exist. This section shows you how to create new objects and how to interact with them.

You can create a new object in two ways: (new ClassName optional-args) and (ClassName. optional-args):

(new String)

; => ""

(String.)

; => ""

(String. "To Davey Jones's Locker with ye hardies")

; => "To Davey Jones's Locker with ye hardies"

Most people use the dot version, (ClassName.).

To modify an object, you call methods on it like you did in the previous section. To investigate this, let’s use java.util.Stack. This class represents a last-in, first-out (LIFO) stack of objects, or just stack. Stacks are a common data structure, and they’re called stacks because you can visualize them as a physical stack of objects, say, a stack of gold coins that you just plundered. When you add a coin to your stack, you add it to the top of the stack. When you remove a coin, you remove it from the top. Thus, the last object added is the first object removed.

Unlike Clojure data structure, Java stacks are mutable. You can add items to them and remove items, changing the object instead of deriving a new value. Here’s how you might create a stack and add an object to it:

(java.util.Stack.)

; => []

➊ (let [stack (java.util.Stack.)]

(.push stack "Latest episode of Game of Thrones, ho!")

stack)

; => ["Latest episode of Game of Thrones, ho!"]

There are a couple of interesting details here. First, you need to create a let binding for stack like you see at ➊ and add it as the last expression in the let form. If you didn’t do that, the value of the overall expression would be the string "Latest episode of Game of Thrones, ho!" because that’s the return value of push.

Second, Clojure prints the stack with square brackets, the same textual representation it uses for a vector, which could throw you because it’s not a vector. However, you can use Clojure’s seq functions for reading a data structure, like first, on the stack:

(let [stack (java.util.Stack.)]

(.push stack "Latest episode of Game of Thrones, ho!")

(first stack))

; => "Latest episode of Game of Thrones, ho!"

But you can’t use functions like conj and into to add elements to the stack. If you do, you’ll get an exception. It’s possible to read the stack using Clojure functions because Clojure extends its abstractions to java.util.Stack, a topic you’ll learn about in Chapter 13.

Clojure provides the doto macro, which allows you to execute multiple methods on the same object more succinctly:

(doto (java.util.Stack.)

(.push "Latest episode of Game of Thrones, ho!")

(.push "Whoops, I meant 'Land, ho!'"))

; => ["Latest episode of Game of Thrones, ho!" "Whoops, I meant 'Land, ho!'"]

The doto macro returns the object rather than the return value of any of the method calls, and it’s easier to understand. If you expand it using macroexpand-1, you can see its structure is identical to the let expression you just saw in an earlier example:

(macroexpand-1

'(doto (java.util.Stack.)

(.push "Latest episode of Game of Thrones, ho!")

(.push "Whoops, I meant 'Land, ho!'")))

; => (clojure.core/let

[G__2876 (java.util.Stack.)]

(.push G__2876 "Latest episode of Game of Thrones, ho!")

(.push G__2876 "Whoops, I meant 'Land, ho!'")

G__2876)

Convenient!

Importing

In Clojure, importing has the same effect as it does in Java: you can use classes without having to type out their entire package prefix:

(import java.util.Stack)

(Stack.)

; => []

You can also import multiple classes at once using this general form:

(import [package.name1 ClassName1 ClassName2]

[package.name2 ClassName3 ClassName4])

Here’s an example:

(import [java.util Date Stack]

[java.net Proxy URI])

(Date.)

; => #inst "2016-09-19T20:40:02.733-00:00"

But usually, you’ll do all your importing in the ns macro, like this:

(ns pirate.talk

(:import [java.util Date Stack]

[java.net Proxy URI]))

The two different methods of importing classes have the same results, but the second is usually preferable because it’s convenient for people reading your code to see all the code involving naming in the ns declaration.

And that’s how you import classes! Pretty easy. To make life even easier, Clojure automatically imports the classes in java.lang, including java.lang.String and java.lang.Math, which is why you were able to use String without a preceding package name.

Commonly Used Java Classes

To round out this chapter, let’s take a quick tour of the Java classes that you’re most likely to use.

The System Class

The System class has useful class fields and methods for interacting with the environment that your program’s running in. You can use it to get environment variables and interact with the standard input, standard output, and error output streams.

The most useful methods and members are exit, getenv, and getProperty. You might recognize System/exit from Chapter 5, where you used it to exit the Peg Thing game. System/exit terminates the current program, and you can pass it a status code as an argument. If you’re not familiar with status codes, I recommend Wikipedia’s “Exit status” article at http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Exit_status.

System/getenv will return all of your system’s environment variables as a map:

(System/getenv)

{"USER" "the-incredible-bulk"

"JAVA_ARCH" "x86_64"}

One common use for environment variables is to configure your program.

The JVM has its own list of properties separate from the computer’s environment variables, and if you need to read them, you can use System/getProperty:

➊ (System/getProperty "user.dir")

; => "/Users/dabulk/projects/dabook"

➋ (System/getProperty "java.version")

; => "1.7.0_17"

The first call at ➊ returned the directory that the JVM started from, and the second call at ➋ returned the version of the JVM.

The Date Class

Java has good tools for working with dates. I won’t go into too much detail about the java.util.Date class because the online API documentation (available at http://docs.oracle.com/javase/7/docs/api/java/util/Date.html) is thorough. As a Clojure developer, you should know three features of this date class. First, Clojure allows you to represent dates as literals using a form like this:

#inst "2016-09-19T20:40:02.733-00:00"

Second, you need to use the java.util.DateFormat class if you want to customize how you convert dates to strings or if you want to convert strings to dates. Third, if you’re doing tasks like comparing dates or trying to add minutes, hours, or other units of time to a date, you should use the immensely useful clj-time library (which you can check out at https://github.com/clj-time/clj-time).

Files and Input/Output

In this section you’ll learn about Java’s approach to input/output (IO) and how Clojure simplifies it. The clojure.java.io namespace provides many handy functions for simplifying IO (https://clojure.github.io/clojure/clojure.java.io-api.html). This is great because Java IO isn’t exactly straightforward. Because you’ll probably want to perform IO at some point during your programming career, let’s start wrapping your mind tentacles around it.

IO involves resources, be they files, sockets, buffers, or whatever. Java has separate classes for reading a resource’s contents, for writings its contents, and for interacting with the resource’s properties.

For example, the java.io.File class is used to interact with a file’s properties:

(let [file (java.io.File. "/")]

➊ (println (.exists file))

➋ (println (.canWrite file))

➌ (println (.getPath file)))

; => true

; => false

; => /

Among other tasks, you can use it to check whether a file exists, to get the file’s read/write/execute permissions, and to get its filesystem path, which you can see at ➊, ➋, and ➌, respectively.

Reading and writing are noticeably missing from this list of capabilities. To read a file, you could use the java.io.BufferedReader class or perhaps java.io.FileReader. Likewise, you can use the java.io.BufferedWriter or java.io.FileWriter class for writing. Other classes are available for reading and writing as well, and which one you choose depends on your specific needs. Reader and writer classes all have the same base set of methods for their interfaces; readers implement read, close, and more, while writers implement append, write, close, and flush. Java gives you a variety of IO tools. A cynical person might say that Java gives you enough rope to hang yourself, and if you find such a person, I hope you give them a hug.

Either way, Clojure makes reading and writing easier for you because it includes functions that unify reading and writing across different kinds of resources. For example, spit writes to a resource, and slurp reads from one. Here’s an example of using them to write and read a file:

(spit "/tmp/hercules-todo-list"

"- kill dat lion brov

- chop up what nasty multi-headed snake thing")

(slurp "/tmp/hercules-todo-list")

; => "- kill dat lion brov

- chop up what nasty multi-headed snake thing"

You can also use these functions with objects representing resources other than files. The next example uses a StringWriter, which allows you to perform IO operations on a string:

(let [s (java.io.StringWriter.)]

(spit s "- capture cerynian hind like for real")

(.toString s))

; => "- capture cerynian hind like for real"

You can also read from a StringReader using slurp:

(let [s (java.io.StringReader. "- get erymanthian pig what with the tusks")]

(slurp s))

; => "- get erymanthian pig what with the tusks"

In addition, you can use the read and write methods for resources. It doesn’t really make much difference which you use; spit and slurp are convenient because they work with just a string representing a filesystem path or a URL.

The with-open macro is another convenience: it implicitly closes a resource at the end of its body, ensuring that you don’t accidentally tie up resources by forgetting to manually close the resource. The reader function is a handy utility that, according to the clojure.java.io API docs, “attempts to coerce its argument to an open java.io.Reader.” This is convenient when you don’t want to use slurp, because you don’t want to try to read a resource in its entirety and you don’t want to figure out which Java class you need to use. You could use reader along with with-open and the line-seq function if you’re trying to read a file one line at a time. Here’s how you could print just the first item of the Hercules to-do list:

(with-open [todo-list-rdr (clojure.java.io/reader "/tmp/hercules-todo-list")]

(println (first (line-seq todo-list-rdr))))

; => - kill dat lion brov

That should be enough for you to get started with IO in Clojure. If you’re trying to do more sophisticated tasks, definitely check out the clojure.java.io docs, the java.nio.file package docs, or the java.io package docs.

Resources

- “The Java Virtual Machine and Compilers Explained”: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=XjNwyXx2os8

- clojure.org Java interop documentation: http://clojure.org/java_interop

- Wikipedia’s “Exit status” article: http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Exit_status

Summary

In this chapter, you learned what it means for Clojure to be hosted on the JVM. Clojure programs get compiled to Java bytecode and executed within a JVM process. Clojure programs also have access to Java libraries, and you can easily interact with them using Clojure’s interop facilities.

The print book longs for you to own it

The print book longs for you to own it

OMG what!? Another book!?

OMG what!? Another book!? Great mama of the bahamas! Learn about reducers!

Great mama of the bahamas! Learn about reducers!